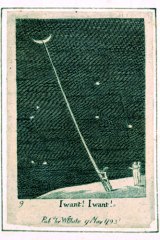

One of the most curious and evocative images in all of William Blake’s vast output of poetry,illustrated books, engravings and paintings is an engraving measuring two by two-and-a-half inches. This was part of a tiny book intended for children called The Gates of Paradise.Published in 1893, it contains 18 images, each with a short caption. This particular image shows a small figure standing at the bottom of a long ladder leaning against the moon. He is watched by a couple who stand aside, holding one another. At the bottom, in bold printing,are the words, “I want! I want!”

I was introduced to this small image several years ago by a friend, Kim Townsend, who teaches English at Amherst College. Recently, in the midst of teaching my sculpture class here at Marlboro, I came across it again. I was using a book called William Blake: His Art andHis Times, by David Bindman, to show students Blake’s images of figures in gestural postures.The students were engaged in finding active poses for life-size cardboard figure sculptures.I often use Blake and a number of other artists from across the history of art as examples of the potential of human gesture and posture to communicate. For the purposes of the class,I was showing several of Blake’s more complex images, but in turning the pages I saw the little images from The Gates of Paradise again—and their power caught me by surprise. I stopped class, and the discussion that followed took us far from the subject of sculpture.

The image we focused on is more emblematic than rendered, more of a cartoon than a drawing, it emphasizes its message yet has a sly and powerful visual presence. For Blake,word and image were always united. His books are diminished when either poems or images are isolated from each other. Blake is unique among Western artists in that both his writing and his art have had vast influence. Blake’s effect on artists has been to encourage many to refigure the world at mythic scale, to imagine the human form as much as to observe it,and to connect one’s visual world with ideas and beliefs.

Importantly, Blake’s drama includes two other characters. The little man is not alone as he starts his impossible climb but is watched by an audience of two, who cling to each other in relative safety. Despite their blank faces, they seem to be scared by his want. They gesture in his direction, recognizing his courage, but seem content to remain earthbound. One student in my class suggested that because they have each other their desires are fulfilled.Like many of us, they are hesitant, blank and caught up in the passive remove of witness rather than the engagement of action.

The discussion in class ranged widely but essentially became an effort to think about the many ways we are defined by the idea of want. We are born wanting, and in seeking fulfillment of our many wants we encounter all of life. We want sustenance. We want connection.We want love. We want learning. It may be the most human of our urges. We want more than we can ever contain. The word want does not simply mean desire, but includes as well the idea of lack. Not only does Blake’s little man want to climb to the stars but he lacks the stars.He is in need of them. As he stands at the base of his impossibly tall ladder and looks up at the night sky, he wants to climb, but in spite of his foot mounting the first rung, he remains at the bottom of the ladder. His cry of want is both hopeful and pathetic. As lovers we want union but are always alone. As students we want knowledge and experience but must make choices that deny whole realms of possibility. As seekers after something real we want to understand yet find ourselves limited in perspective. As artists we want to take that which we are compelled by and make it actual, yet we find that translation painful, incomplete and never-ending. Want drives us and disappoints us. Despite the divided nature of want, we continue and achieve.In some ways, it seems a wonderful and simple encapsulation of our humanity.

What occurred to me in my classroom that day was that all of us there, in fact all of us atMarlboro, are involved in a search for real things—we desire things and people to care about,we want things to understand. It seems necessary to desire in the desperate, even foolish, way of Blake’s little man in order to make progress toward our goals. In fact, the object of our wants is constantly shifting. There will always be new areas of learning to investigate, new work to make,new people to engage. Education is never complete. Our choices are many and the competition for our attention extreme. To want with passion is what we most essentially need in order to make progress through experience. It is necessary to want in order to learn.

William Blake sought a language for visionary ideals in words and images—“a restoration in the light of art.” He mistrusted much of church doctrine, of philosophical wisdom and of scientific truth. He felt that he could not understand reality without trust in visions and the imagination. It was his great gift to be so completely directed. Despite the nearly complete indifference of society, Blake labored for a lifetime at his wants. He lived in poverty, surviving by engraving the work of other artists and through the generosity of a few friends. That he kept his desire alive through it all is a mystery. We spent a good deal of time in that class marveling at his example. For most of us, circumstance intervenes. Wants get compromised. The struggle that most challenges us over time is to keep our wants alive.

After class I hurried to photocopy the image, and it has been on my office door ever since. It acts as a creed and a challenge to me as I enter each day. This all sounds vaguely like a sermon, but given Blake’s intensity of beliefI’m sure that my sentiments are appropriate. What he manages to do in this modest image is to keep the characters human and appealing while still fulfilling their emblematic role. To me this is the best kind of creed—simple and small, yet connected to all things.A grand image in a tiny children’s book. The whole of human endeavor, measuring two by two-and-a-half inches.In its face I am humbled and inspired.

Tim Segar, under most circumstances now a sculptor, began as a passionate, romantic, and thoroughly ridiculous poet whose sudden self-awareness in college sent him, thankfully, straight into the art studio. He has not been tempted since to return to writing poetry except privately, sometimes in short poems written in search of titles for his sculpture. He maintains an abiding love of poetry, though, and has written about it on several occasions, notably in ”Reality and the Nature of Perception in Wallace Stevens’ ‘An Ordinary Evening in New Haven,’” a talk he gave at Cornell University in 1999 and at Marlboro on several occasions.